A Deep Dive: Gertrude Stein

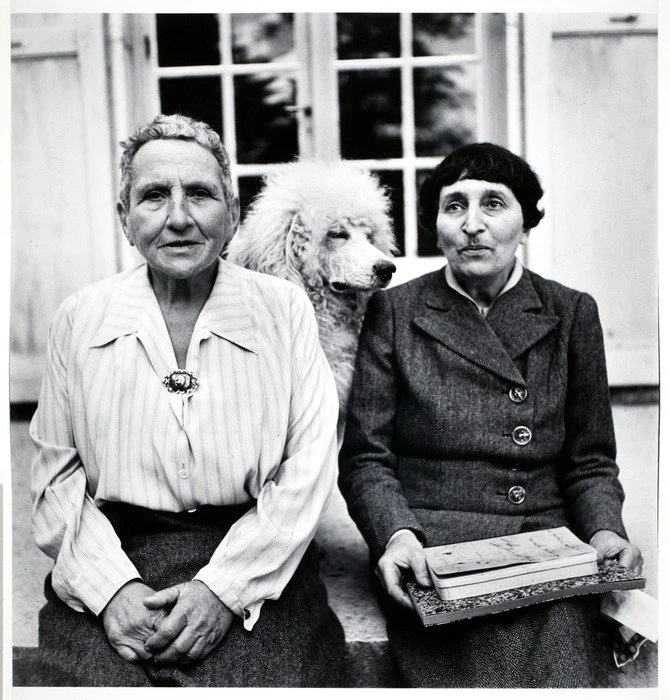

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas with Basket (Photo by Carl Mylan, 1944) Image from ICP.org

It was recently my honor to be a guest on the Potent Podables podcast hosted by my friends and fellow Jeopardy! alumni, Kyle and Emily. As part of the podcast, I wrote a “deep dive” about the subject of one of that week’s Jeopardy! clues, Gertrude Stein. Here’s the text, but I encourage you to listen to the episode as well, and subscribe to the podcast if you enjoy Jeopardy! or just learning new things.

I am very excited to bring you a deep dive on the modernist writer, Gertrude Stein!

Gertrude Stein was born on Feb. 3, 1874 in Allegheny City, which is now part of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to German-Jewish parents. The youngest of five children, she grew up speaking both German and English. When Gertrude was three, her parents moved the family to Vienna, then Paris, in order to give their large family a taste of European culture and sophistication. Later in life, Gertrude said that this was how Paris got into her blood. After four years abroad, the Steins moved back to California and settled in Oakland. Although she was criticized for later saying of Oakland, “There is no there there,” Gertrude had been happy there and possibly was referring to the fact that her family had scattered and her childhood home was gone. By the time she was 17, Gertrude was an orphan, and she was sent to live with her uncle in Baltimore.

While living in Baltimore, Gertrude got to know the Cone sisters, Claribel and Etta. The Cones were art collectors and frequent travelers to Europe who regularly hosted salons on Saturday evenings. These salons served as inspirations for the ones that Gertrude would later host in Paris.

Gertrude was very close to her older brother Leo and missed him terribly when he went away to Harvard. Even though she had only completed one year of high school and did not know Latin, which was at that time a requirement for admission, Gertrude somehow managed to get herself enrolled at Radcliffe to be closer to Leo. In a 1959 Harvard Crimson profile of Gertrude which called her the “most brilliant woman student,” a member of the college administration is quoted as saying, "She didn't like us and we didn't care for her."

While at Radcliffe, Gertrude studied psychology and published a paper with another student about the theory of automatic writing, or writing without the input of the conscious mind. This is often cited as being influential on Gertrude’s later writing style, although she said later on that she knew that there could be no writing without the conscious mind being involved.

Gertrude graduated from Radcliffe in 1898. She next attended Johns Hopkins Medical School, but became discouraged and depressed and did not finish her course of study. In those days, there were very few women studying medicine, and she clashed often with the male students and faculty. During this time, she gave a controversial lecture to a Baltimore women’s group criticizing the idea of women's economic dependence on men. At Johns Hopkins, Gertrude was involved in an unhappy love triangle with two other women, which she fictionalized in the novel Q.E.D.

In 1902, Leo moved to London, then Paris in 1903, and Gertrude went with him. In Paris, Gertrude and Leo lived together until 1914 and built a world-class art collection including works by Cezanne, Gauguin, Picasso, and Renoir. Their reputation as art collectors grew thanks to their friendship with dealers and critics, many of whom visited their Saturday evening salons. During this time, Gertrude wrote some of her most famous works, including Three Lives, Tender Buttons, and The Making of Americans.

In 1907, Gertrude met the love of her life, Alice Babette Toklas, the day after Alice arrived in Paris. The two fell in love at first sight, and Alice moved in with Gertrude and Leo in 1910. They remained together until Gertrude’s death in 1946.

Leo had discouraged Gertrude’s writing, but Alice was always supportive. She encouraged Gertrude to write by maintaining their household and arranging for the publication of Gertrude’s works. Gertrude published her book Tender Buttons in 1912. Tender Buttons established Gertrude’s style as doing with language what the emerging Cubist movement was doing for art. Her verbal collages produced one of the lines she is best known for, “Rose is a rose is a rose,” from the poem “Sacred Emily.”

In 1914, Leo moved to Italy and the collection was divided between the two siblings. He left Gertrude all the Picassos except a portrait Picasso had done of Leo. After some extended trips elsewhere in Europe, Gertrude and Alice came back to Paris to join the war effort in 1915. Although Gertrude did not know how to drive, she bought a Ford truck, got one of her friends to teach her how to drive, and immediately volunteered to drive supplies to hospitals. Gertrude called her truck “Auntie” after her aunt Pauline, “who always behaved admirably in emergencies and behaved fairly well most of the time if she was properly flattered.”

In the 1920s, Gertrude and Alice presided over their salons, where artists and writers gathered, many of them American expatriates. As Gertrude saw it, they were a “lost generation” too young to have fought in World War I and therefore having nowhere to focus their political and social energies. Ernest Hemingway was a regular attendee, although Alice grew jealous at the time he spent with Gertrude. Allegedly, Gertrude helped Hemingway to rewrite and revise A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway also used Stein’s words as the epigraph for The Sun Also Rises.

In 1926, Gertrude lectured at Oxford and Cambridge on her experimental, immersive theory of writing. She remained an experimental writer mainly published by small literary magazines and read by only a few. Because Gertrude wanted to be better known, she took the advice of friends like publisher Bennett Cerf and critic Carl Van Vechten and decided to write her memoir. However, in typical contradictory fashion, Gertrude wrote her memoirs through the eyes of Alice.

Gertrude wrote her most famous book, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in 1933. Alice and Gertrude went on an extended lecture tour in America after the book’s publication, after satisfying themselves that the food would be acceptable by asking the hotels they would stay at to send them menus of their available dishes. Although this was her best-received book, Gertrude felt as though writing it might have compromised her art.

Gertrude adhered to a strict schedule with plenty of time for writing, made possible by Alice’s behind-the-scenes efforts. Gertrude spent her mornings writing letters, playing with Basket, the dog, and reading. After lunch, she ran errands, and wrote whenever the mood struck her. She never made any appointments or received visitors before 4 pm. Gertrude and Alice were devoted to their dogs, both white standard poodles. When Basket died in 1937, they bought another white poodle that they named Basket II.

The most problematic part of Gertrude’s legacy remains her support and embrace of the fascist movement in France. She was, to put it simply, a collaborator with the Vichy government. Gertrude was encouraged to return to America but refused, stating that she was “particular about her food.” Alice and Gertrude retreated to a rural house. Gertrude and Alice were Jews living in a dangerous time and place for Jews and were in a relationship that would not be supported or understood in the United States. Gertrude’s friendship with prominent political figure Bernard Fay gave her special privileges like the right to drive her car. That friendship also helped her to save her property, including her sizable art collection, from being seized. Gertrude was only one of several modernist writers and philosophers who embraced fascism, thinking it was a way to get back to what they considered a superior, pre-industrial America.

After the war, Gertrude welcomed many young American soldiers to her home and befriended them. She later wrote about them in the 1946 book Brewsie and Willie, and about her experiences during both World Wars in Wars I Have Seen, published in 1945.

Gertrude died on July 27, 1946 after an operation for stomach cancer at the American Hospital in Paris. Before going into surgery, she asked Alice “What is the answer?” When Alice didn’t answer, Gertrude asked, “In that case, what is the question?” Although the exact wording is unclear due to Alice’s having given different accounts, those were the last words Gertrude Stein ever spoke.

Gertrude left her estate to Alice, but their relationship had no legal basis. Because of that, Gertrude’s family took control of her assets, including the art collection, and left Alice destitute. Alice wrote three books after Gertrude’s death and lived with the help of donations from friends until her death in 1967. She and Gertrude are buried side by side at Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

In 1992, a life-size statue of Gertrude Stein was erected in Bryant Park in Manhattan. It is based on a 1923 model created by sculptor Jo Davidson.